In a nutshell: Joe Strummer is why I teach. He exhorted (“Let fury have the hour!”); he provoked (“Anger can be power–Do you know that you can use it?”). That’s what we should do as teachers in front of the classroom, just as Strummer did onstage and on vinyl. This post turned out to be minimally about the actual Joe Strummer, and mostly about all the metaphorical Joe Strummers in my life.

The April 20 edition of Soundcheck, WNYC’s daily talk show about music hosted by John Schaefer, featured a segment about a new book and documentary, Let Fury Have the Hour, by writer, filmmaker, producer, and visual artist Antonino D’Ambrosio, about the late Joe Strummer, lyricist, rhythm guitarist, lead singer, and social conscience of the 1970s and 80s punk rock band, The Clash. In a very real sense, Joe Strummer is why I teach. I thought that that perhaps surprising fact deserved a post here on Pedagogishnes, so here goes.

The April 20 edition of Soundcheck, WNYC’s daily talk show about music hosted by John Schaefer, featured a segment about a new book and documentary, Let Fury Have the Hour, by writer, filmmaker, producer, and visual artist Antonino D’Ambrosio, about the late Joe Strummer, lyricist, rhythm guitarist, lead singer, and social conscience of the 1970s and 80s punk rock band, The Clash. In a very real sense, Joe Strummer is why I teach. I thought that that perhaps surprising fact deserved a post here on Pedagogishnes, so here goes.

As readers of Pedagogishness are aware, my skin in the teaching game is critical pedagogy, helping students think critically about axes of privilege and oppression in a world where people are defined by their race, class, gender, sexuality, nationality, immigration status, and other historically specific, socially constructed, and above all highly POLITICAL categories. But where I first learned about critical pedagogy was not really from Paolo Friere’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Rather, it was from Joe Strummer. More accurately, a string of Joe Strummers, for whom Joe Strummer may serve as something of a cipher and a synecdoche, starting perhaps with–well, I wasn’t planning to say this initially, but starting perhaps with my mother, Lee Broder (1921-2005).

My mom, the daughter of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, had not quite a high school education. Nevertheless, she was a voracious reader of books, newspapers, and magazines and took me to every major museum and cultural attraction in New York City by the time I was ten years old. My father, who himself had only a high school education, died when I was 11, and my mom worked in various kinds of clerical jobs at places like A&S Department Store and Metropolitan Life Insurance Company to keep me fed, clothed, and sheltered. This 50 year-old widow (I was a “change of life” baby) packed me onto buses to destinations from Niagara Falls to Washington, DC (with several stops along the Great White Way, including my first-ever Broadway musical, the ever fabulous and life-changing A Chorus Line) all before I was 16 years old. I’ve often faulted her for the stumbling blocks she put in my path, but from the long view of my own middle age, I must admit, Mom was my very first Joe Strummer.

Then, in fifth grade, I had a teacher named Mrs. Levy, who was divorced with two preschool-age children who sometimes joined the class for picnic-in-the-park type outings. By the end of the school year Mrs. Levy was Mrs. Cohen (a much better match, it turned out, as Phyllis and Ted are still together 40 years later, with lots of grand-kids). Mrs. Levy was dedicated and innovative in a way that seems intimately connected to the ethos of that era. That year our class was responsible for putting on the big school play, and Mrs. Levy led us in writing our own script, based on a bunch of folk protest songs she taught us while strumming on her guitar–“Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream” is the only one I can remember offhand. A space traveler named Gulliver lands on a planet called 1776 where none of the people have any rights. Gulliver tells them about freedom and the Declaration of Independence, and they stage a revolution and start a democracy. I played Gulliver, of course!

That year, somebody in the administration got the idea to mix some of the “lower performing” Puerto Rican kids from the rough part of Coney Island in with the rest of us “higher performing,” mostly Jewish kids (and Timmy Yee, who was ethnically Chinese but said “Oy vey” when bad things happened to good people) from the Luna Park housing development in, well, the other part of Coney Island. Apparently nobody else really wanted them. Oddly enough, the under-performing Puerto Rican kids all did great that year, with a teacher who didn’t assume there was anything wrong with them and treated them like capable and intelligent human beings. I remember the day after West Side Story was on TV, and all the Puerto Rican kids were suddenly Sharks. We Jewish kids (and Timmy Yee) were hardly Jets, but there was still some wariness between us that fall. By the spring we all had a lot of respect and affection for each other. That was the year my father died. Mrs. Levy, who became “Phyllis” after the school year ended, kept an eye on me for years to come. She and Ted took me along with their own kids to see my first-ever production of The Nutcracker at Lincoln Center. Phyllis Cohen was my next Joe Strummer.

In junior high I had a bunch of great English teachers, but the standout superstar was Vera Goldberg, another divorced Jewish mother, but much more Fran Drescher to Phyllis Levy’s…Debra Messing? (I wonder if Joe Strummer was Jewish?) Mrs. Goldberg made us write–all the time. Poems, stories, plays. We were constantly reading our own work aloud. Always making various kinds of creative presentations, individually, in teams, in groups, with props. Mrs. Goldberg (who later became Mrs. Fried, another successful second marriage that seems to have more than made up for the failed first) inspired a lot of people. One of her students a few years after me was this guy named Darren who grew up to make a few films–Requiem for a Dream, The Wrestler, Black Swan…. A few months ago, after Darren gave her a call to say a much-belated “Thank You,” Vera (I always ended up on first-name bases with my Joe Strummers) started calling old students to find out what other creative geniuses she had spawned. Needless to say, I felt a little inadequate. I didn’t even finish my MFA until I was 44, or my PhD until I was 49, and I haven’t published anything longer than a poem or a two-thousand word essay. But Vera was pleased nevertheless. Vera Fried was my next Joe Strummer.

(NOTE: Anita Malta and the late Judy Slater were no slouches as English teachers at J.H.S. 303, either. Ms. Malta taught me to write both essays and poems, and Miss Slater had us reading Antigone in eighth grade, in response to which I wrote my own Greek tragedy about a modern hero named Superman, complete with a chorus of citizens of Metropolis. Superman flew around saving lives all over the world while a meteor approached Earth, confident that he could fly up and destroy it at any time. But it turned out to be made of Kryptonite, and Superman fell to earth, defeated by his hubris, and doomed to watch Metropolis destroyed, along with Lois and Jimmy and everyone he loved. The tragedy was introduced by a scholarly essay explaining how I combined elements of modern mythology with the Aristotelian unities of time, place, and action. Miss Slater scrawled across the lavishly decorated cover, “This could have been written by a graduate student!” In fact, I think I later handed that paper in for a class on Greek tragedy with Seth Benardete, or was it Jacob Stern…?)

I went to the amazing (and, amazingly, now shut down for poor performance) 1970s experiment in secondary education, John Dewey High School, where among my outstanding teachers was George Bader, who taught a social studies course called Problems of the American Economy (at Dewey, you didn’t just have tenth-grade social studies, you had courses with names and topics). Mr. Bader (yes, we made those jokes) was tall and lanky and long-haired in a sort of Shaggy-from-Scooby-Doo kind of way, and seemed to wear the same sweaty and apparently never washed Tweetie Pie tee shirt to class every single day. He strode around the room like a giant smelling the blood of an Englishman, climbing over desks, waving his arms around in exuberant mock disbelief tinged with earnest distress as he enlightened us as to travesties of American government and politics like COINTELPRO and the Trilateral Commission. I was actually a bit skeptical of Mr. Bader at the time, because he had groupies, and I was suspicious of people with groupies, and because I wasn’t sure I was as radical as Mr. Bader seemed to think I should be (I kind of wanted Gerald Ford to win in 1976, and thought his campaign-destroying debate comment about the autonomy of Eastern European states was visionary, not foolhardy; I think I was proven somewhat correct in that youthful assessment by the election of a certain Soviet Bloc-buster name Ronald Reagan four years later, not to mention the events at the Gdańsk Shipyard). But the fact is, I sort of grew into George Bader. Now I am the one who climbs over desks and waves my arms around, telling my mythology students that Eros is both a floor wax AND a dessert topping (don’t worry, there will be a Pedagogishness post on that one at some point, too). George Bader was my next Joe Strummer.

My final Joe Strummers came along during my college years. One of them was, of course, Joe Strummer. I’m no expert on Joe Strummer or The Clash. For facts and interpretation you should just read D’Ambrosio’s new book, and see the film if it’s playing at a theater or available for download near you. And it’s not even, or even primarily, Joe Strummer who was my main Joe Strummer. I was much more into the much more cerebral Gang of Four, whose Joe Strummer and Mick Jones were named Jon King and Andy Gill (and whose Topper Headon was an awesome Hugo Burnham). But as I said at the outset, Joe Strummer is cipher and synecdoche for many Joe Strummers, men and women who exhorted me and provoked me and taught me that anger can be power, if only I can figure out how to use it.

A number of my facebook friends (who are also real-life friends, regardless of how much or how little I’ve seen them in thirty years) will be quite justly outraged if I do not credit Stuart (Shlomo) Felberbaum for punking me out in the late 1970s and early 80s (okay, maybe punked out is a strong term, but you know what I mean–we did wait on line all night in the pouring rain for tickets to see The Clash at Bonds in 1981). So here is credit where credit is due. I would never even have heard of The Clash, Gang of Four, Public Image Limited, or, for that matter, Jean-Luc Godard or Robert Rauschenberg, had it not been for Stuart Felberbaum, my high school co-best friend (with Steven Cohen) from Brighton 13th Street. Nor would I have studied Latin or Greek. Stuart Felberbaum was one of my very most very biggest very best Joe Strummers.

And finally, one last Joe Strummer. As an undergraduate at Columbia University, I had an English Professor named Jeffrey Perl, first for Introduction to Literary Theory, and then for the second semester of the year-long Modern British Literature sequence (another pretty awesome professor named David Damrosch taught the first half). Some of the main ideas of Prof. Perl’s take on modernism are captured in this 1994 article by Jewel Spears Brooker in the South Atlantic Review (Vol. 59, No. 2, pp. 53-74):

The necessary context for the modernist obsession with history includes the nineteenth-century invention of the “Renaissance,” a topic explored in Jeffrey Perl’s The Tradition of Return. Perl points out that although the Renaissance happened in Italy in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, it was invented in France in the early nineteenth. The concept migrated from France to Germany and thence to England. As conceptualized in Jacob Burckhardt’s monumental Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, published in Germany in 1860, and Walter Pater’s The Renaissance, published in England in 1873, the period became an important and far-reaching reference point in the history of ideas. History was thought of in three large blocks–ancient, medieval, and modern. The third block, defined as a rebirth of the first, begins with the Renaissance. The very idea of the modern, then, includes the idea of a return.

The modernists, then, were obsessed with classical antiquity. I’m not sure if this is what Prof. Perl was trying to tell me, but the message I took away was that a knowledge of Greek and Roman language, literature, and culture was essential for an understanding of modernity. It was Jeff Perl’s modern British literature class, then, that pushed me not only to study Greek and Latin (Stuart Felberbaum was already urging me in that direction), but to get a master’s degree and, ultimately, a doctorate in classics.

But more than that, Prof. Perl taught me that cultural connections, historical connections, and political connections are ultimately different dimensions of the same human fabric, like matter, energy, space, and time are ultimately different dimensions of the same physical universe. This is what all of my Joe Strummers have been saying all along: The Clash, Gang of Four, Jean-Luc Godard, Raymond Williams, Fredric Jameson, Terry Eagleton, Pablo Picasso, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Eve Sedgwick, Judith Butler, Gayle Rubin, Esther Newton, Adrienne Rich…the list can go on and on, and does go on and on. Now, as I finish this year of teaching both classical mythology and modern European literature at the University of South Carolina, I wonder if maybe one or two students are leaving campus this spring having learned this lesson, or something quite like it, from me. Maybe I finally get to be somebody’s next Joe Strummer.

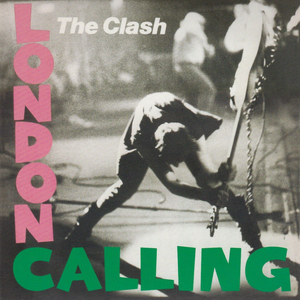

Now that all that sappy memorabilia is out of the way, check out this classic punk rock anthem of critical pedagogy, “Clampdown,” from the 1979 album London Calling. NOTE: I really want to include a live performance, but all the live videos of this song on YouTube SUCK! One must not forget that the Clash started out as TERRIBLE musicians. The performance at BONDS in NYC in 1981 would be great, if Strummer didn’t mess up all the lyrics to his own song [and it only has audio, anyway, no video]. I’ll keep looking, but for now, the studio version is still the best. If you click through to the YouTube page for this video, it also has the lyrics.